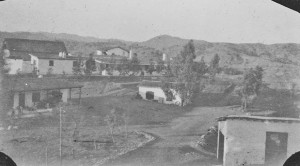

“Ah! La Iglesia!” A smile creased the stern face of the Paraguayan guard at the sentry post. In his hands he held my little album of pictures open to the one with my mother standing beside the little old church in the monastery courtyard where they had lived in the 1920s. Now gesturing amiably, he indicated that we should park the car outside the barbed wire enclosure circling the compound. Just across the road were the jumbled slag heaps of the old Skouriotissa mine. Instead of the open semi-arid landscape of the old pictures, giant

eucalyptus trees arched overhead. Natalie Hami, who had set aside her day as a reporter for the Cyprus Mail, nudged the car into place.

Natalie had written an article in April about the Skouriotissa mine, which had just produced its 50,000th ton of copper using modern techniques of extraction and refinement. I found out about it through Pippa Vanderstar, our friend in the States who had done her doctoral research on Cyprus in classics and archaeology. I wrote to Natalie and she responded enthusiastically that she would like to do a human interest story on our quest when we arrived. We had met with her that morning at her office in the old town of Nicosia. Over a Starbucks (the one across from the McDonald’s) we had reviewed our strategy for the day and set out for the hour’s trip west to the old mine, which was now situated on the southern. Greek-speaking, edge of the Green line dividing Cyprus. Indeed, the location of the mine, though dormant at the line’s drawing in 1974, had dictated where the line would go.

As we neared the mine we decided to find a place for a little lunch. I spotted a brand new sign next to the road indicating a restaurant. We pulled off on a gravel road, rounded a little hill and saw only a sparkling new go-cart track and restaurant. Yes, in the middle of the proverbial Nowhere. Just opened. No one was in sight but two staff members, evidently from eastern Europe, in a spotless restaurant with glistening icons on the walls. So we had some sandwiches overlooking the track, with the dry hills and fields stretched out toward the Turkish side. In the distance, nothing had changed from my mother’s pictures, though I knew it was unlikely I would see the oxen and camels she had seen. Below us was the artifice of contemporary amusement, lined with old tires waiting to be kissed by gleefully careening youngsters. We left non-plussed about their business plan and prospects, laughing at the incongruities of time and space in Tom Friedman’s Flat Earth.

When we got to the mine entrance, no one was in the guardhouse. We looked around, first toward the large shop where a mechanic was working on a huge excavation machine, and then up the mountain of crushed ore above us. I coaxed Natalie into heading up the hill, pursued, it seemed by one of those earth-moving leviathans. We found a line of cars parked amidst buildings at the top and I asked a lone worker where the offices were. The contemporary brick building he pointed to was just ahead, “Hellenic Copper Mines Ltd.” in large letters on its roofline. While we struck up conversation with some of the staff using the old pictures, Natalie went upstairs to arrange a later meeting with the Director, whom she had spoken to earlier.

As always, the pictures opened a door to excited comparisons with today’s environment and activity. It also revealed that some of the people connected to today’s mine had ancestors who had worked there, perhaps even with my grandfather. Their directions had led us to the sentry at the UN compound.

As we entered the compound I saw a wall that figures in one of the old photographs, the trees now towering overhead. The guard followed us to indicate how to go up to the church and we ascended some steps under the curious eyes of some other soldiers. We were at the back of the church. Next to it was a colonnaded structure from the old pictures. We walked around the church to the courtyard where my mother had played. There was no well or flowers now. Only a white picket fence, a palm tree, and a large tent-like structure where their main quarters had been. But the church was the same. Even the pillars on the adjoining building were the same.

In response to my English questions a friendly Ecuadoran solder emerged to talk with us and digest the gap between my old pictures and the present reality. The walls that had sheltered monks and miners now held soldiers who had sought to guard a brittle peace for thirty-eight years. I leaned against the wooden post supporting the church’s front roof and realized how few words had come down to me to tell of what took place here ninety years before. Indeed, how few words had come down to us from its building some six hundred years earlier.

In response to my English questions a friendly Ecuadoran solder emerged to talk with us and digest the gap between my old pictures and the present reality. The walls that had sheltered monks and miners now held soldiers who had sought to guard a brittle peace for thirty-eight years. I leaned against the wooden post supporting the church’s front roof and realized how few words had come down to me to tell of what took place here ninety years before. Indeed, how few words had come down to us from its building some six hundred years earlier.

As Sylvia asked whether we could go inside the church, its administrator came to check on things and admitted us into its dark interior. Achilleas showed us the icons and spoke of his life-long association with the church. His son had been baptized recently at the font in  the corner. In my mother’s time it must have had only candles for illumination. Now the hand hewn beams overhead supported an ornate electric chandelier. Sylvia lit two candles – “from the holy lamp is best,” he said – in memory of my grandparents, my mother, and our return, and we silently breathed in the history of this place. Achilleas had to leave to pick up his son at school, so we stepped back into present time and its numbing light, gazed around the compound once more, waved goodbye to the soldiers and descended back to the entrance.

the corner. In my mother’s time it must have had only candles for illumination. Now the hand hewn beams overhead supported an ornate electric chandelier. Sylvia lit two candles – “from the holy lamp is best,” he said – in memory of my grandparents, my mother, and our return, and we silently breathed in the history of this place. Achilleas had to leave to pick up his son at school, so we stepped back into present time and its numbing light, gazed around the compound once more, waved goodbye to the soldiers and descended back to the entrance.

The pilgrimage was not complete. We went back to the mine offices for an unforgettable conversation that I will recount in my next installment.

Red Clay, Blood River

Red Clay, Blood River

congratulation for your article. It’s amazing that foreign people write about our history and our village. I grow up in Katydata and my father worked at the mine, too. The church is symbol for us, we visit it very often, we baptism our children there and we respect the “Panayia Skouriotisa”.

George

I continue to be fascinated with the intertwining of ancient, “recent,” and your personal history. You must find it very fulfilling.

I loved your article. I grew up in Katydhata and used to visit the church at Skouriotissa on a regular basis. Both my parents worked at the mine (in the offices) until 1974 when we left Cyprus for England. I still visit often as I still own property near the mine (in fact the house opposite the entrance to the mine) which used to belong to my grandparents.

It was good to see the old photos too – my grandmother would have been just 11 years old when your mother was in Cyprus.

I love how the old photos continue to open doors for you. No language barrier there or a picture is truly worth a thousand words.